Alum reflects on early CT coverage of the gay liberation movement

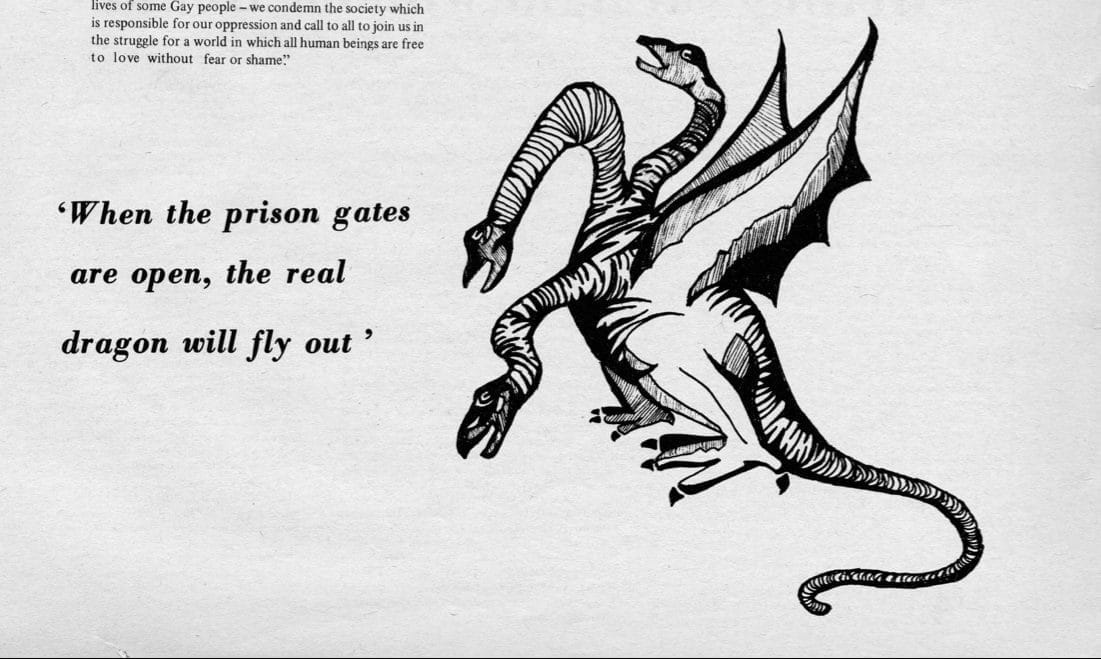

A 1971 CT article featured an illustration of a hydra with a HO Chi Minh quote used widely by revolutionaries. CT archives

This story is part of The Commonwealth Times’ special coverage in honor of its 50th anniversary.

Walter Chidozie Anyanwu, Contributing Writer

The Stonewall riots of the late ‘60s ushered in an era of inquiry into what it meant to be a member of the LGBTQ community in the U.S. At that time, many other groups of people were struggling for acceptance in the country, but the least visible of them were people who identified with the gay liberation movement.

For many whom Stonewall might’ve affected, it was a time for change: change not just in the way the country treated gay people, but in the way they were seen as well.

In December 1971, a few years after Stonewall, The CT ran a story on the progression of gay liberation efforts in Richmond.

Mike Whitlow was one of two reporters who went out to conduct interviews with VCU students.

“We thought it would be an interesting story to cover,” Whitlow said. “I was totally naive [to the issue]. It was a very personal confrontation of my own naivete about such things.”

Whitlow said covering this story gave him the opportunity to both change personally and also understand the importance of the movement, especially to those who would’ve been directly affected by identity bias.

Richmond was a bit moderate at the time, but still far from what it is today in terms of acceptance of sexual identities. A lot of what used to be considered non-normative behavior was frowned upon, so members of the LGBTQ+ community often found themselves in hostile situations.

The members of Richmond’s Gay Liberation Front met with Whitlow and his colleagues in an apartment on Grove Avenue. The meeting yielded one singular theme: They just wanted to be who they were, Whitlow said.

The reporters were drawn to the story because of the relative invisibility of the movement in Richmond, mostly because it was dwarfed by the progressive public’s preoccupation with civil rights and women’s rights.

“We were at the front end of a little story,” Whitlow said. “We wanted to ask, ‘What’s going on? Why can’t these people be themselves?’”

It has been more than 40 years since the story came out, and Richmond has grown more and more progressive. Whitlow believes it has something to do with VCU’s presence. The university, he said, became an incubator for all sorts of ideas and points of view.

The ‘70s and ‘80s were periods of radical social reform, with victories claimed on many fronts by minority groups, but it hasn’t been more than a decade since the LGBTQ+ community saw big changes such as the legalization of same-sex marriage.

“Are we at the right place yet? I don’t know, I don’t have a really good insight,” Whitlow said. “But to me, the benefit of that story [was that] it contributed to that gumbo that was VCU at the time.”

While his story did not receive any significant public backlash, Whitlow believes it had something to do with the conversation around sexuality being brought to the forefront of social discourse in Richmond.

“I hope that that little article had an influence on [peoples’] worldview,” Whitlow said.