Press Box: The Minneapolis Miracle – A reflection on the long term prognosis for American football

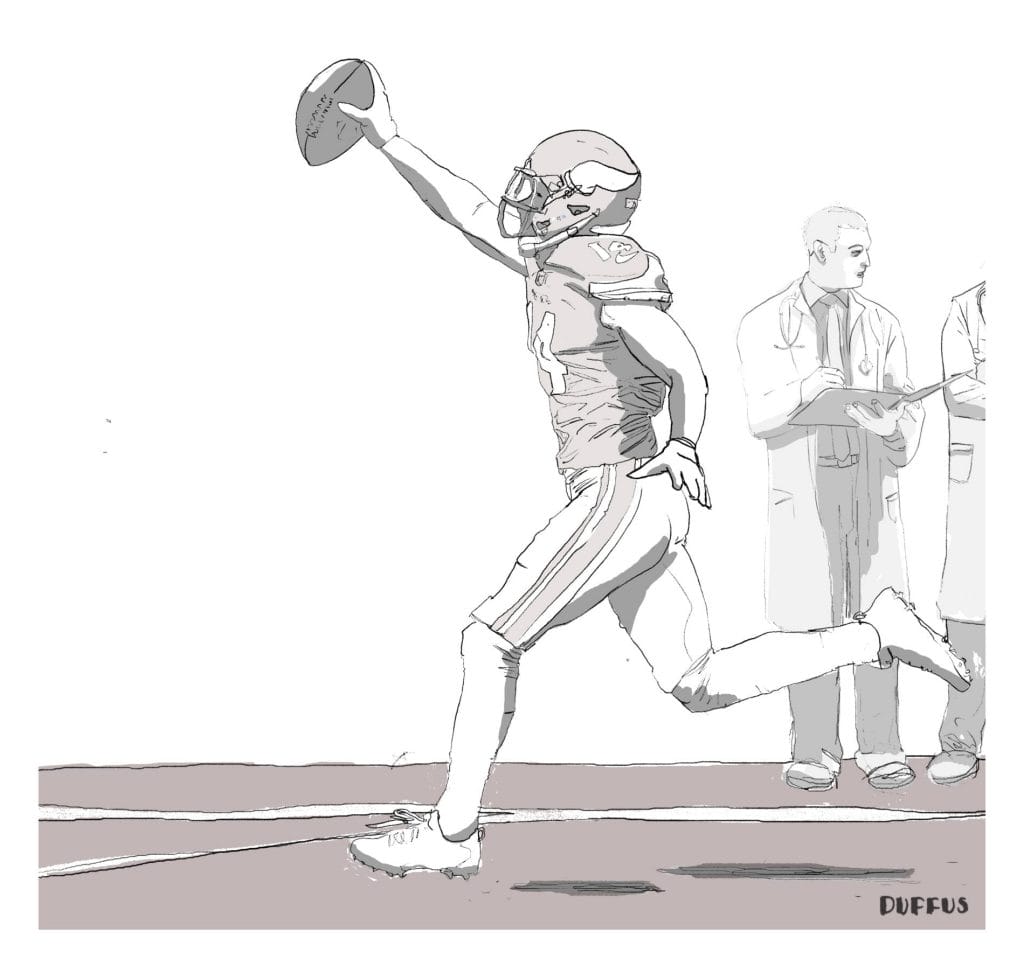

Illustration by Ian Duffus

While Minnesota Vikings’ wide receiver Stefon Diggs turned upfield with zeros on the clock and a swath of gloriously green grass in front of him during the final play of his team’s divisional round victory over the New Orleans Saints, football’s lifespan stood frozen in time.

That’s not to say one play or player could ever begin to change the time frame encompassing American football’s diminishing future. It can, however, give cause for reflection on the prognosis for an issue that threatens the life of our beloved game — concussions and how to manage them.

Diggs gave the Vikings a 29-24 win, sending them to the NFC championship and allotting Minnesota the chance to become the first team to ever host a Super Bowl. His game-winning 61-yard touchdown came as time expired and will go down as one of the most inspiring, improbable and exciting plays in the sport’s history.

However subliminal, the “Minneapolis Miracle’s” prestigious place in the NFL canon cannot do anything to change the current regression of football’s cultural spirit. This reality is what came to mind as I watched Diggs’ teammates celebrate with him in the endzone.

The discovery of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) has forever changed the game, and for good reason. The Alzheimer’s-like disease is developed as a result of repeated head injuries normally tied to jarring, head shaking, torque-based motion – not necessarily impact – which is highly common on a football field. The condition has claimed the lives of former NFL players such as Chicago Bears safety Dave Duerson and San Diego Chargers linebacker Junior Seau.

Dr. Ann Mckee, professor of neurology and pathology at Boston University, conducted a study of CTE for CNN in 2015. Her team found indications of the disease in 44 out of 55 college football players.

“To find it in 44 players suggests that it isn’t a rare condition,” McKee said. “Just a condition that we didn’t look for before.”

The shocking reality that physical trauma experienced in normal football games can cause long term, life threatening brain disease has, to this day, not fully sunk in for most football fans. Heck, Will Smith played the lead role in a movie about the revelation. It has captured the hearts and minds of the American public, to the point that an ongoing debate about the long term prognosis of the sport is now a daily news item.

Even hall of fame players are taken aback by the newly discovered safety hazards associated with football. Former Green Bay Packers quarterback Brett Favre told Fox Business in March he would be very reluctant to let his own children play the game he loves.

“If I had a son, I would be very, very reluctant to let him play (football), knowing what I know now — which is not a lot. For us, there is still so little about CTE we know. But we do know it’s not good, especially for youth.”

I love football to death, as does Favre, obviously. Moments like the Minneapolis Miracle are simply religious experiences for me and much of America.

I will probably not let my children play football until they are 18. There are simply other, equally magical sports for them to spend their youth enjoying. I could not, in good faith, put a helmet on my children when doctors studying this disease are making proclamations such as those made in McKee’s findings.

“I think it’s becoming more and more clear that the developing brain is more susceptible to concussions; it has a delayed recovery,” McKee said. “We really need to limit the amount of head contact that young children and adolescents are experiencing.”

Favre recently released a documentary titled “Shocked: The Hidden Factor in the Sports Concussion Crisis.” In it, the cheese-head icon details his work with Brock, a company that markets a padding material designed to reduce the amount of concussion athletes experience from hitting their heads on field turf. The 48-year-old Favre — who says he is already experiencing the effects of CTE — has made it his mission to explore ways in which football can be rendered a safer sport, since retiring from the gridiron himself.

“I was always great with names and faces,” Favre said. “But that’s not so much the case anymore. Sometimes I’ll be talking, and it’s like I’ll know what I want to say, but I just can’t get it together in my head and make it come out.”

Recognizing and mitigating this frightening reality portrayed by Favre — and many athletes who suffer from CTE — must be the priority going forward for anybody else who felt some type of way watching Diggs cross that goalline. Like Favre, every-day fans are coming to the understanding that, as it stands right now, football as we know it will not survive these discoveries. There are too many ex-players complaining of severe mental and emotional distress, and too many doctors telling us CTE is the reason why for anybody to turn a blind eye in good conscious.

A massive overhaul in American football’s safety precautions is immeasurably necessary in order for the sport to remain in existence long term.

Currently, the prognosis is critical — and that’s what popped into my head watching Diggs score that immaculate touchdown.

I asked myself if the clock was ticking on moments like this.

I asked myself what I would say if my child were watching with me and posed the question, like I had countless times as a child to my parents, if I could be a football player and do awe-inspiring things like that.

I think I would tell her or him no…and that tears me apart.

Zach Joachim, Sports Editor