Natalie Barr, Staff Writer

Black maternal mortality rates have increased over the decades, according to the CDC’s Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System reports.

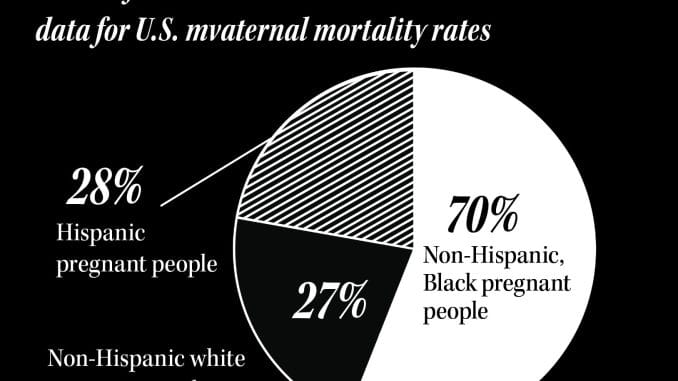

Non-Hispanic, Black pregnant people had the highest maternal mortality rate at about 70%, whereas the rate for non-hispanic white pregnant people was about 27%, according to 2021 CDC data from U.S. Maternal Mortality Rates. Data also showed the mortality rate for Hispanic pregnant people was 28%.

The maternal mortality rate for Black communities is three to six times greater than what white pregnant people experience, according to Tashima Lambert Giles, VCU Health assistant professor in the obstetrics and gynecology department.

“If we are not focusing on that [disparities affecting Black maternal health], then unfortunately, we’re gonna have worse outcomes for Black moms,” Lambert Giles said.

Social determinants of health, such as access to quality education, quality health care, an individual’s neighborhood and economic stability, are why Black communities experience maternal mortality at a higher rate, according to Lambert Giles.

Racism also plays a big part into why Black pregnant people still face a higher maternal mortality rate, she said.

“That’s the reason why when people talk about this, we don’t exclude the conversation of racism, because we see how institutional and structural racism have actually created this unfortunate crisis,” Lambert Giles said.

Lambert Giles believes the first step to improve Black maternal health is “recognizing, addressing and accepting” — this is a problem to be able to find solutions, she said.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists formed task forces to improve the standard of care while ensuring all hospitals maintain the standard despite their demographic, Lambert Giles said. Individualized patient care and understating factors impacting one’s pregnancy, childbirth and post birth are beneficial to providing solutions, she said.

Sequoi Phipps-Hawkins, doula and director of communications for Birth in Color RVA, was “shocked and appalled” with the maternal mortality rate Black mothers face in this country, she said.

“I just wasn’t okay with that,” Phipps-Hawkins said. “I wanted to see what things were already happening and what I could add to help curb that, and hopefully, help eliminate and eradicate that maternal mortality rate.”

Many Black mothers will get written off from their care providers because providers think Black people have a higher pain tolerance, or complain about pain that “will just go away,” Phipps-Hawkins said.

Mothers of color are dying from preventable causes, Phipps-Hawkins said, such as:

- Post-surgical birth complications of severe abdominal pain

- Chest pains that turn out to be pulmonary embolism

- Preeclampsia, even postpartum preeclampsia, a condition when your body produces too much protein causing an individual’s blood pressure to spike and can lead to stroke, death or organ failure

“If we boast about the health care that we have in this country, our moms shouldn’t be dying from preventable causes,” Phipps-Hawkins said.

Phipps-Hawkins trained to become a doula to be able to provide a positive impact for an individual’s birth and post experience, she said.

Through organizations like Birth in Color, Medicaid recipients are now able to be reimbursed for doula services, which was not the case until last year; recipients can be assigned a doula to offer support and help during the entirety of an individual’s pregnancy, Phipps-Hawkins said.

The organization works with hospitals across the state to do diversity, equity and inclusion training to create more awareness on Black maternal health, and offers doula training to allow doulas to be present in the birthing rooms to promote a positive experience, according to Phipps-Hawkins.

“We talk about joy all the time here because we’re doing so much of this gritty hard work, then we see these numbers that can be frustrating and heartbreaking,” Phipps-Hawkins said. “The reality is birth and welcoming a newborn into your family should be a joyous occasion.”

Juanita Street, a first-time mom, heard about Birth in Color RVA three months into her pregnancy after a friend sent her an Instagram post about doula applications; Street had already been thinking about getting a doula and wanted to apply for one, she said.

Street knew of complications and risks Black women could face during pregnancy and childbirth and was anxious about the process, she said. Street did experience complications during her pregnancy, she said.

“If I had not had a doula with me, I felt like my experience would have been a little bit different. Not in the sense of it could have been worse, but it could not have been as satisfactory,” Street said. “I would not have had somebody behind me to advocate for me through my experience.”

Street was able to have a close relationship with her doula, Phipps-Hawkins, she said. Street appreciated how her doula would check in with her throughout the entire process, celebrate milestones and would be there to answer questions about symptoms she felt, according to Street.

“A lot of women don’t realize that they could have access to something like this. They don’t realize how important it really could be to their mental health during pregnancy,” Street said.

Street wants women to look at all resources available to them during pregnancy and consider getting a doula to have as a support system, and to always advocate for oneself when something does not feel right in your body, she said.

“It can be a struggle at times. If you feel like you’re by yourself, but when you look out for other options and other resources, it’s definitely helpful,” Street said.

Leave a Reply